Why volunteer for a semi-starvation experiment?

Participant motives in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment and what they teach us

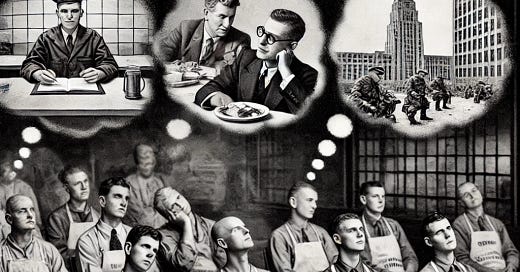

In my previous post, I wrote about the participants of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, a World War II semi-starvation experiment conducted to create medical knowledge for famine relief in war-torn Europe. I argued that the men who participated in the experiment did so voluntarily. As I read through the process of how these men were selected, I came across a section that discussed the motives of these men.

Here is my paraphrased list:

1) Some felt they filled no real need in their assigned civilian roles, and they wanted to contribute to society.

2) Some wanted to experience levels of discomfort similar to what soldiers and civilians experienced in war-torn areas.

3) Some wanted to contribute to scientific knowledge.

4) Some wanted to test their limits, alleviate their guilt for holding a pacifist position, or gain recognition for their self-sacrificial behavior.

5) Some were attracted by educational opportunities, like the possibility to enroll in courses at the University of Minnesota.

6) Some were attracted by the idea of living in a big city.

7) Some were curious about what it feels like to starve and saw value in building self-discipline through their participation.

Can we trust these motives?

Before we draw any lessons from a list of motives, we need to start with a basic question. Is it plausible that these were the real motivations of the volunteers? If not, there is no point in analyzing them any further.

One concern when asking people about their motivations is that they lie. They say things that sound good, and claiming altruistic motives sounds better than claiming self-interested ones. This means that if a list only includes noble and altruistic motives, we should typically treat it with skepticism. Reassuringly, this list includes self-interested motives, such as living in a city or taking advantage of educational opportunities. Even though we cannot look into people’s heads to gauge their real motives, the presence of self-interested motives makes the list at least plausible.

With the plausibility prerequisite out of the way, let’s turn to the real question: Why is it important to know participants’ motives?

This knowledge matters for two reasons. First, it can help us design programs that attract more participants. Second, if we highlight the diverse motives participants have, we make it clear that excluding potential participants based on having the “wrong” motive is costly.

More motives, more people

People have the intuition that more program features mean more participants. In the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, participants could enroll in courses at the University of Minnesota, a fairly unusual feature for a medical experiment. From a pure recruitment standpoint, adding this feature made sense only if some participants would not have volunteered in the absence of this feature.

It’s difficult to figure out which program features were crucial to recruiting participants, and which ones could have been eliminated. To complicate matters further, we know only the self-reported motivations of the self-selected group of people who ended up volunteering for the experiment. We know some features were attractive (i.e., people volunteered), but we don’t know which ones, and which alternative features (that had not been included in the experiment) would have worked just as well or maybe even better. In other words, designing an experiment with the right set of features is challenging, especially if it’s a one-off and highly atypical experiment testing the effects of semi-starvation.

Fortunately, there is a low-cost way to attract more participants to medical experiments: don’t reject people who want to participate.

Fewer motives, fewer people

It’s quite common for experiments, or for programs more broadly, to allow only participants with certain motives. You want to participate in a medical experiment for money, or fame, or to test your physical and emotional limits? Tough luck. Only altruists need apply.

Motive-based exclusion is frequently justified by a variant of the following: “People should do the right thing for the right reason.” I agree. And everybody should be happy, smart, kind, rich, and live forever. Aspirational goals are important, of course, but policies should consider trade-offs and real-life constraints.

The altruism requirement is a policy that sounds good. We all want to hear about heroic men and women who self-sacrifice at the altar of the common good and contribute to a great breakthrough in medicine. Such people exist, but they are rare. The potential participant pool is substantially larger if we add to these Good Samaritans those people who want to participate for money, to test themselves, or for any other reason.

Listing the diverse motives of the volunteers, as was done in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, makes the costs of motive-based exclusions more transparent. It’s easy to imagine that fewer men would have volunteered had the researchers excluded all those who had non-altruistic motivations, such as wanting to test their physical limits.

Of course, describing an unrestricted program will sound worse at a cocktail party: “Yeah, this guy joined our experiment to win over a girl, that one to earn money for an exotic holiday, and the third one was just bored.” We can find participants’ motives selfish, impure, or outright bizarre. But signing up more participants allows us to conduct medical experiments faster. Speeding up medical progress, in turn, saves many lives. Compared to the millions of lives that faster medical innovation can save, our misgivings about volunteers’ motives don’t matter. When we face a trade-off between program aesthetics and progress, we should prioritize progress.