The Minnesota Starvation Experiment

How to recruit volunteers for a 6-month semi-starvation experiment

The year is 1945. A group of emaciated men are walking along the banks of a river as part of a medical experiment. The topic of the experiment? The effects of semi-starvation. Yet contrary to what one might expect, these men are not in the Third Reich. They won’t provide testimony at the Doctors’ Trial, nor will they be cited as cases that necessitate the Nuremberg Code. They are in the US. The medical experiment they participate in is called the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, and these men are volunteers.

The goal of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment was to understand the physiological and psychological changes people go through in semi-starvation and to develop effective refeeding strategies. Participants ate a controlled, semi-starvation diet for 6 months, followed by a rehabilitation period.

Developing scientific knowledge in this domain was pressing given the famine-like conditions in parts of Europe at the time. However noble the goal, starving to advance science is not a path many take voluntarily. This raises a fundamental question: How do we know these emaciated men were volunteers—rather than pseudo-volunteers?

To answer this question, I’ll examine the relevant details of the experiment and evaluate the presence of three factors that can invalidate consent: 1) force was applied to secure someone’s participation; 2) material details of the experiment were withheld from the participant; and 3) the person was not capable of consent due to their age or other factor.

The details I report about the experiment come predominantly from Chapter 4 of The Biology of Human Starvation, a two-volume, ~1400-page book the researchers wrote about the experiment in 1950.

1. Were they coerced?

Study participants came from the Civilian Public Service (CPS). This was a program consisting of 12,000 conscientious objectors to the war, most of them associated with the historic peace churches. These men had been drafted just like millions of their countrymen, but instead of being sent overseas to fight, they worked as firefighters and did other socially valuable work—including as volunteers in medical experiments. The book CPS Story, a work about the history of this program, mentions various such cases. For example, to understand how infectious hepatitis spreads, CPS volunteers were “inoculated with blood plasma suspected of being infectious, swallowed nose and throat washings and body wastes of infected patients, and drank contaminated water.”

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment was one of these studies that needed volunteers. To recruit participants, the researchers created a brochure and circulated it in the CPS camps where most of these men lived. Interested volunteers then sent their written applications to the researchers. More than 100 men applied.

Out of these men, those who had been “particularly recommended by their churches and the camp directors” were selected for an interview and underwent a battery of examinations, including “complete clinical, radiological, biochemical, physiological, and psychological examinations”. In the end, 36 men were approved to participate in the experiment.

All this evidence suggests no one was forced to apply and participate in the experiment. But the right to be free from coercion doesn’t last only until the paperwork is signed. Participants should be able to withdraw their consent and leave the experiment whenever they want. This is, in fact, what happened with some of the participants who broke their diet and were excused from the experiment. In total, the researchers reported data from 32 men.

One could accept these men were free from coercion before and throughout the experiment, but what about the other prerequisites for consent?

2. Were they informed?

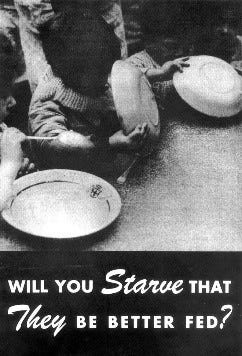

To evaluate how much these men knew about the experiment, we need to return to the interview conducted with participants during the selection process. In the words of the researchers, “[the participants] were specifically cautioned about the possible dangers and the physical and mental discomfort inherent in the experiment.” Transcripts of these conversations are not available, so we don’t know what exactly this entailed. But circumstantial evidence suggests that participants understood the most important feature of the experiment. Recall that the experiment was advertised via a brochure. This was the cover of the brochure:

Telling prospective participants that they will starve to help others seems like a fair description of a semi-starvation experiment.

3. Could they consent?

The only possible objection that remains is that these men may not have been in a position to consent. After all, it was common around that time to use non-consenting populations in medical experiments, like people locked up in prisons and mental hospitals. Were these men mentally ill or otherwise incapable of consent?

Quite the opposite. By all accounts, their cognitive abilities were way above average. Participants had an average of 15.4 years of formal education, and 18 out of the 32 men had college degrees. As a comparison, roughly 5-6% of their cohort had a university degree at the time.

Their test performance tells a similar story. The US military used standardized testing (the Army General Classification Test) to evaluate the cognitive ability of all its recruits. The mean score of the participants was about 2 standard deviations above the mean for all draftees. One way to look at this result is to say that if typical draftees were deemed capable enough to fight a war (and potentially die) overseas, then these 32 men were clearly capable of deciding whether to participate in a medical experiment or to continue with their lives in a CPS camp.

Many years on

Consent needs to be contemporary. How participants think about the voluntariness of their participation many years later can provide no definite proof either way. However, follow-up information about these participants is still valuable. In an oral history project conducted almost 60 years after the experiment, 18 participants (out of the 19 alive) were interviewed about their experience. When asked about what they knew about the experiment before signing up, this is how Max Kampelman, one of the participants who later became a prominent diplomat during the Cold War, summarized the information he had been given:

They explained what was going to happen. There was nothing held back. They explained that they could not assure me that there would be no permanent damage... They did not know what would happen. This is what they were trying to find out . . . really they emphasized the discomfort... this was not going to be an easy task down the road.

—Excerpt from Kalm and Semba (2005)

Conclusion

When we learn that a medical experiment was conducted around 1945, we are rarely surprised positively. The story typically involves medical experimentation against someone’s will. Alternatively, the participants were children, mentally ill, prisoners, or others who were not in a position to consent. At the very least, they were misled about the material aspects of the experiment.

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment was unlike these studies: it recruited consenting participants of above-average intelligence who understood what they signed up for. This shows that recruiting volunteers for challenging medical experiments can be done ethically. This achievement, accomplished 80 years ago, during a world war no less, raises a challenging question: If ethical recruitment was possible then, why do today’s regulations often stop informed and consenting adults from becoming volunteers in crucial medical experiments?